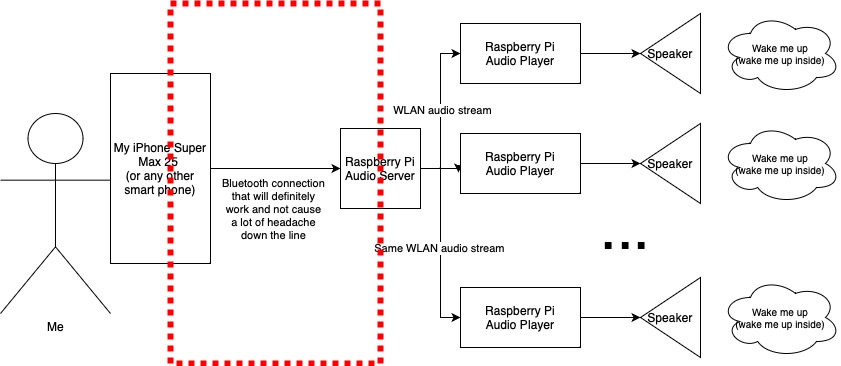

Check out the previous part of the Aioli Audiostreamer saga here. In case you don’t want to check it out, here’s a quick recap: I started a new project in which the goal is to stream audio from one Raspberry Pi to another over an IP network. The last time we got the streaming to work in theory, but the practical part of it was (and is still) missing. This time we’re not going to to address that.

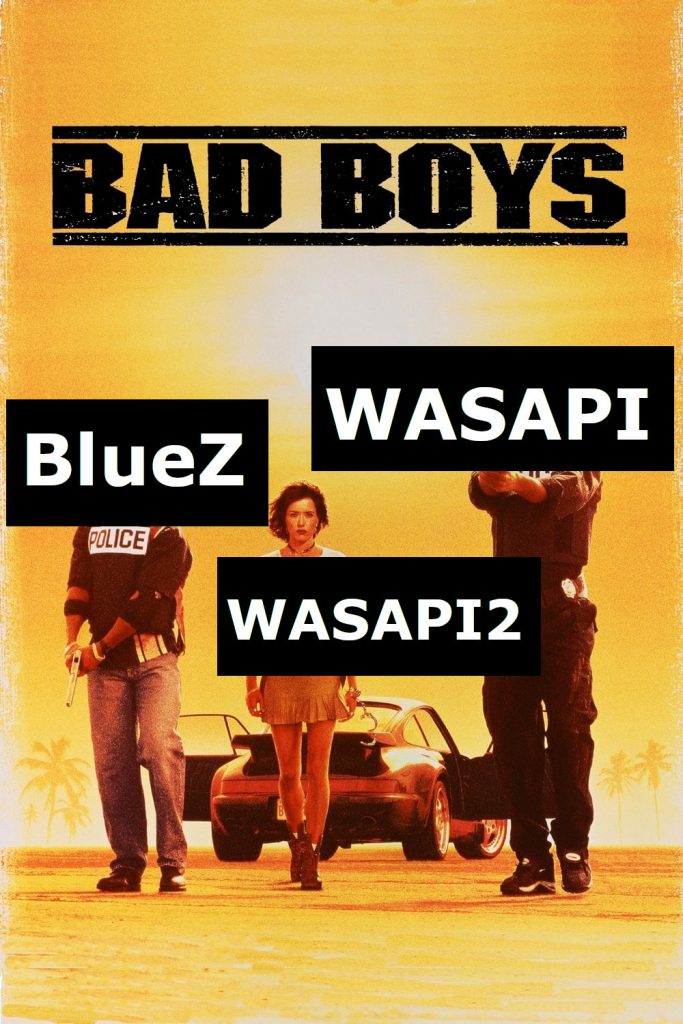

Instead of focusing on getting the streaming working robustly and automatically, I chose to add a Bluetooth connection between the Raspberry Pi controller device and an external audio source. This way the system can stream something else than just the audio files present in the controller device. Here’s the graph with a chunky red line showing what’s the focus for today:

Unfortunately, this means confronting my old nemesis: BlueZ stack. Or Bluetooth in general. Something about it rubs me the wrong way. I’m not sure if it’s actually that bad. However, every time my headphones fail to connect to my phone I curse the whole protocol to the ninth circle of hell. Which happens every single morning. And it’s still the best choice for this kind of project. But yeah, plenty of that coming up.

Bluetooth Connectivity

The first step is making our Raspberry Pi audio server advertise itself as a Bluetooth device wanting to receive audio: headphones, speakers, or anything along those lines. In theory, this sounds like a lot of work, but once again, the open-source community comes to the rescue. This bt-speaker project makes a Raspberry Pi act as a Bluetooth speaker, which is exactly what we want. The phone (or some other audio source) can connect to the bt-speaker daemon running on Raspberry Pi and stream audio to it. bt-speaker then outputs the received audio to the desired audio device.

The program required some tweaking for cross-compilation, and some things weren’t quite as generic as they could have been, causing some QA errors in Yocto. However, it mostly worked quite nicely out of the box. I guess because the bulk of the program is written in Python there are not that many compilation issues to wrestle with. There was also one codec that needed to be compiled, and then there was the issue of figuring out the correct dependencies, but all in all fairly simple stuff. Yocto recipe can be found here.

The Actual Troubles

What actually took a long time was getting the start-up script working. I’m still sticking to SysVinit for simplicity, which means that I ended up using start-stop-daemon to launch the program. However, it turned out Busybox’s implementation of start-stop-daemon was missing the -d/--chdir option. bt-speaker loads a codec from a relative path, meaning that the program fails at start-up because it’s launched from the root directory. Because I’m not much of a Python programmer, I chose to patch the feature into Busybox instead of doing the sensible thing and installing the codec into the correct location and fixing bt-speaker. An open-source contribution to Busybox coming soon I hope.

Well, after that came the second problem: the Bluetooth chip in Raspberry Pi wasn’t stable during the startup. The script starting BlueZ worked well, and the bt-speaker launched successfully as well. However, after a few seconds, the Bluetooth device became undiscoverable. I tried to check all the Bluetooth-related changes that happened during boot in the system: changes in the Bluetooth device information and BlueZ status, reading syslog & dmesg, but no. The Bluetooth chip just reset a few seconds after the BlueZ launched. So I did what any sane person would do: power cycled BT chip as a part of the start-up, added a “reasonable amount” of sleep, and moved on with my life.

The Less Actual Troubles

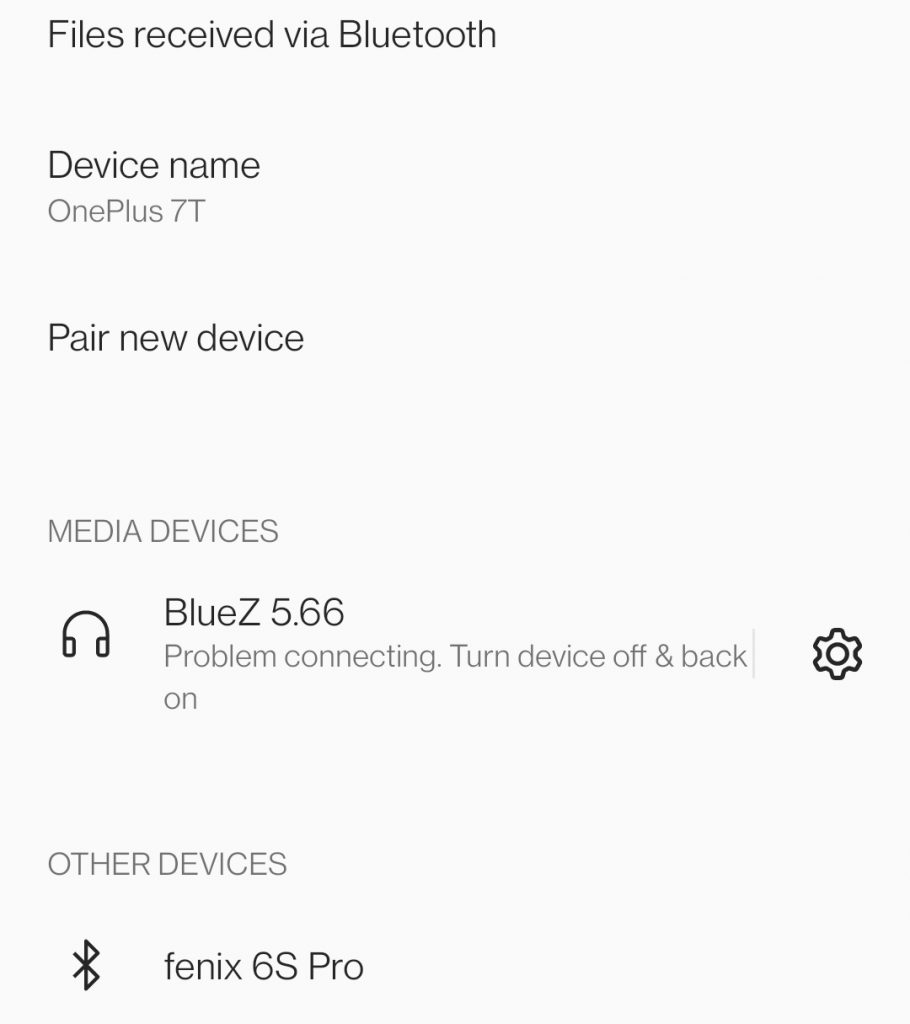

After getting the thing starting automatically during the boot there’s still a small problem. The problems never end with Bluetooth, don’t they? Well, even better, there are two problems. First, for some reason, my phone says that it has trouble connecting to this Frankensteinian BlueZ device. Streaming music from Spotify works nicely though, and even the volume control behaves as expected. So all in all, this sounds like a very typical Bluetooth device already: nothing works, except that it works, except when it doesn’t. I’m not yet sure if this is actually a problem or not to anyone else except my phone.

The bigger issue is that we don’t want the audio to be output from the Raspberry Pi we’re connected to. Instead, we want to stream the audio to the other Raspberry Pis in LAN and have those output the audio. GStreamer has an alsasrc source that can take input from an ALSA device and work with that. However, we have a bit of a mismatch here: GStreamer wants an input device to receive the audio from (e.g. microphone), but bt-speaker generates audio that goes to an output device (e.g. speaker).

Loop Devices to the Rescue!

Loop device is a virtual audio device that redirects audio from a virtual output device to a corresponding virtual input device (or vice versa). This means that we can have a virtual “microphone” that outputs the audio that bt-speaker has been received through Bluetooth. Maybe my explanation just made it worse, the idea is quite simple. This blog post explains the functionality quite well.

To explain more: probing snd-aloop module creates two loopback sound cards, both for input and output (four cards in total). The virtual cards have two devices, and each device has eight subdevices. This results in a lot of devices being created. These devices are special because the output of an output device gets directed to the input of a corresponding input device. For example, if I play music with aplay to card 1, device 0, subdevice 0, the same music can be captured from the input card 1, device 1, subdevice 0. Notice how the device number is flipped. Output to input, and vice versa, as I’ve been repeating myself for two chapters now.

With this method, when bt-speaker uses aplay to output the audio it receives, we can define the output device to be a loopback device. Then, GStreamer can use the corresponding loopback input device to receive the Bluetooth audio and pass it to the LAN. A bit of patching to the bt-speaker, and something like this seems to do the trick:

# Play command that bt-speaker uses when it receives audio

aplay -D hw:2,0,1 -f cd -

# Streaming command to send audio to 192.168.1.182

gst-launch-1.0 alsasrc device=hw:2,1,1 ! audioconvert ! audioresample ! rtpL24pay ! udpsink host=192.168.1.182 port=5001Is This a Good Idea?

I’m not sure. I think it would be possible for the bt-speaker daemon to launch the GStreamer directly once the Bluetooth connection has been initialized. This approach would skip aplay altogether and wouldn’t require the loop devices. However, keeping the Bluetooth and networking separate should keep the system simpler. Both processes do their own thing without knowledge of each other. bt-speaker can output audio without caring if anyone listens to it. On the other end, GStreamer can stream whatever it happens to receive through the loopback device.

This also allows kicking the bt-speaker and GStreamer individually when they eventually and inevitably start misbehaving. The drawback is that GStreamer streams silence if nothing is received from Bluetooth, but I think that’s an acceptable weakness for now. After all, I’ve paid for a WLAN router to route some bits, so I’m going to route them bits, even if they’re all zeros.

I noticed that there actually is a BlueZ plugin for GStreamer. However, it’s labelled as one of the “bad” plugins, and dabbling with such dark magic sounds like a bad idea. If something is labelled “bad” even in the official documentation it’s usually better to avoid it. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the quality itself is bad as the label may also mean a lack of testing or maintenance, but still.

Closing Words

This text was a bit shorter than anticipated, but some things in life are unexpectedly short. Next time we’ll get rid of the static WLAN configuration. Instead, we’ll create a mechanism for passing the SSID and password during run-time. We’ll be doing that mostly because I already started working on that feature. Now I have DHCP servers running amok in my home LAN causing trouble and slowing down development.

One question still remains: does this system contain any code that I have written? Not really at the moment. But in my experience, that’s the story for most of the embedded Linux projects: find half a dozen somewhat working pieces of software and glue them together with some scripts. Until next time!

This blog text is a part of my Movember 2023 series. If you found this text useful, I’d ask you to do “something good”. That doesn’t necessarily mean shoving your money to charities or volunteering weekends away (although those are good ideas), it can be something as simple as asking a family member or colleague how they’re doing. Or it can mean selling your earthly possessions away and becoming a monk. It’s really up to you.